Medicine as war: what M*A*S*H did for the ‘battle’ against COVID

Militaristic language in medicine persists because we see doctors as all-powerful, says Alan Alda

One hot, humid night in the summer of 2020, I sat at a dining room table in a rented cabin off the shores of Lake Winnipeg, and wrote a heartfelt pandemic cri de coeur about a fictional army doctor, one who taught me how we might make it through our COVID “war.”

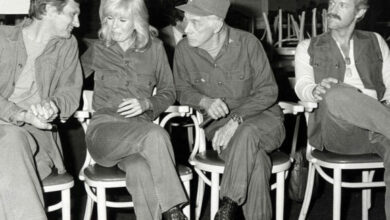

That doctor was Captain Benjamin Franklin (Hawkeye) Pierce, the main character of one of the most beloved television series of all time: M*A*S*H, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in the fall of 2022.

Many beautiful surprises ensued. After the piece was published by The Los Angeles Times, it went viral. In the ensuing weeks and months, I learned there were tens of thousands of people like me — healthcare workers who had been inspired to go into medicine because of Hawkeye’s struggles in Korea, workers who, during the pandemic, found themselves on a very different kind of frontline.

But we weren’t really at war, of course. Certainly not in the way Hawkeye had been.

So where did that war language come from? And why did it seem like it was suddenly everywhere?

How the shadow of war shaped language

Alan Alda, the actor who played Hawkeye Pierce on television, says militaristic language in medicine persists partly because of our psychological need to see physicians as all-powerful gods.

“The idea that some of us regard reacting to an illness as a battle against it… that implies that there are weapons to fight with, and I’ll get better,” Alda, now 87, and an advocate for science communication, told me in our interview.

“But a lot of science in medicine is trial and error. And that’s not comfortable for a lot of us who want the doctor or the scientists to be more like a god.”

The roots of the infiltration of such language also run much, much deeper, and much further back than the travails of Hawkeye’s 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital.

“It’s really tied up with all sorts of big issues in the history not just of medicine but the history of Western society,” said Agnes Arnold-Forster, a historian of health care, medicine, work and the emotions at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

She points out that from the 1600’s onward, as nations’ armies expanded, there was a greater emphasis on medicine and its contributions to saving the lives of soldiers. From then on, the language of medicine and war became inseparable.

Arnold-Forster says that the shadow of war also came to shape the structure — and the culture — of medical education.

“When physicians are learning to be physicians and they’re training, they’re ‘in the trenches’. They’re on the ‘front line’ against a set of structural problems. And that’s new to the 20th century, mainly because the character of health care changes in the 20th century. You have whole state-funded health care systems, which didn’t exist in the 19th century [and] before. And so you need a new language to deal with this new state of affairs.”

Doctors suffer in silence

I have written extensively about the ways in which medical training and practice affected my own physical and mental health. But, unable to grasp the bigger forces at work — the same ones Arnold-Forster has spent her career studying, I often saw these as personal failings.

I didn’t initially recognize how the same personality traits that made me a conscientious and compassionate doctor — in the Hawkeye mould, I hoped — also predisposed me to potential problems further down the road.

These tensions are universal among those who practice medicine, and yet, the culture discourages disclosure of our conflict and suffering, according to internationally renowned trauma expert Dr. Bessel Van Der Kolk, who shared with me that he too had struggled during his early years as a student doctor.

“I often felt in medical school that I’m losing my soul. I’m dealing with all these horribly suffering people. And I was often suffering myself. I needed to shut off my own suffering.”

But medical schools have not historically taught young doctors how to deal with that suffering, or even acknowledged that it exists — one small but important cultural piece of the complex physician burnout puzzle.

Arnold-Forster also says military metaphors normalise a culture of denying the importance of basic physical and emotional needs in medicine. It’s one of her areas of study.

“[It] makes it possible for people to do real damage in and of themselves,” she said. And she points out that this framing never allows people to cope with that damage, or recuperate from it.

Dr. Van Der Kolk agrees.

“I think not making room for people’s needs is very devastating,” he said. “And I think that’s why I see so many physicians who are actually looking for alternative ways of practicing the profession because it’s just too hard to work in a setting where people don’t see you and take your particular needs into account.”

It has all led me to wonder if we should do away with the language of war.

“No matter how you look at it, if you engage in a warrior, you’re looking to cause some people to die,” said Alda, who was honoured with the Screen Actors Guild’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2019, “whereas if you’re engaging in medicine, you’re looking at as many people as possible to live.

“So I can see not liking the implication that it’s drawing on the language of hurt rather than health. Maybe there are ways to do it without suggesting that we’re going to kill something.”

Guests in this episode:

Alan Alda is an award-winning actor, best-selling author, and advocate for science communication.

Agnes Arnold-Forster a historian of health care, medicine, work and emotions at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Dr. Bessel Van Der Kolk is an internationally renowned trauma expert and the author of The Body Keeps the Score.

Dr. Carol Bernstein is a professor of psychiatry in New York City and a former president of the American Psychiatric Association.